By Chaim Seidler-Feller and David N. Myers

Israeli democracy is under threat. Incitement against human rights organizations proceeds with little trace of official censure; cabinet ministers aim to impose new ideological litmus tests in the realm of education and culture; government-sponsored bills place Jews on a higher plane than other citizens, and the State’s Ashkenazi chief rabbi declares that “Israel is first and foremost Jewish, and only then democratic.”

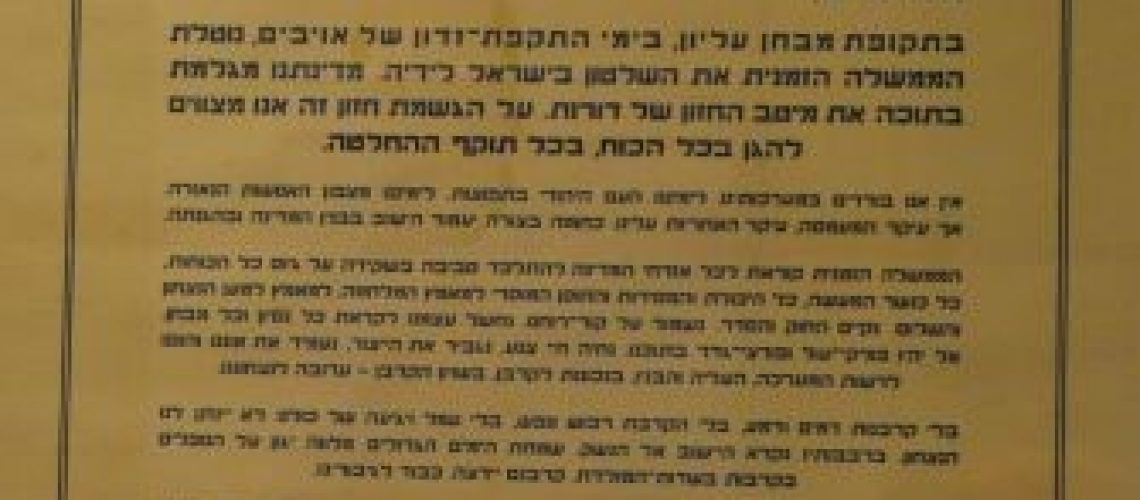

These acts deviate sharply from principles that were clearly and forcefully articulated before, during and after Israel’s Declaration of Independence on March 14, 1948. Those earlier principles, drawn from a range of diverse perspectives, reflected the mix of enlightened Jewish and Zionist ideals at a crucial moment of formation. A number of these first principles figure centrally in a series of broadsides that are held in the personal collection of Chaim Seidler-Feller and are on display at the Yitzhak Rabin Hillel Center for Jewish Life at UCLA. Ahead of Israeli Independence Day, we present excerpts from them in translation below.

Sixty-eight years ago, in the face of intense pressures from within and without, powerful voices were heard calling for the anchoring of robust democratic principles in the foundation of the new State. They figured in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, which called for “complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex.”

Sixty-eight years ago, in the face of intense pressures from within and without, powerful voices were heard calling for the anchoring of robust democratic principles in the foundation of the new State. They figured in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, which called for “complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex.”

On the same day as the Declaration was issued and as the nascent State was confronting the invasion of five Arab armies, the Provisional Government published a decree calling on all residents to prepare for struggle and sacrifice in the coming days. Concomitantly, the decree proclaimed:

Within the confines of our State, citizens of the Arab people continue to live — for most of them this war is loathsome. Their rights as equal citizens we are duty-bound to uphold. We look to peace. Our hands are extended to them as partners in building the homeland.

This striking call to recognize Jews and Arabs as equals was offered in the shadow of the Holocaust and in the face of an ongoing conflict understood as a war of survival. Seven months earlier, an even more soaring expression of this principle appeared in a broadside published on October 19, 1947 in both Hebrew and Arabic by the left-oriented League for Jewish-Arab Rapprochement in Jerusalem. It announced:

JEWS AND ARABS! Let us end this Satanic dance! The Jewish and Arab masses do not want chaos and bloodshed! The Jewish and Arab masses do not want a war of one people against another! The Jewish and Arab masses want a life of peace and creativity, a life of freedom and progress! Whatever the ultimate political outcome of the question of the Land of Israel will be, it will be meaningful only to the extent that it will guarantee peace and cooperation between two peoples whose fate is linked in an unbreakable bond to the fate of the land. Only Jewish-Arab unity can create enduring facts in the Land of Israel; only Jewish-Arab unity can advance this land toward independence and true freedom, toward progress and efflorescence.

JEWS AND ARABS! Let us end this Satanic dance! The Jewish and Arab masses do not want chaos and bloodshed! The Jewish and Arab masses do not want a war of one people against another! The Jewish and Arab masses want a life of peace and creativity, a life of freedom and progress! Whatever the ultimate political outcome of the question of the Land of Israel will be, it will be meaningful only to the extent that it will guarantee peace and cooperation between two peoples whose fate is linked in an unbreakable bond to the fate of the land. Only Jewish-Arab unity can create enduring facts in the Land of Israel; only Jewish-Arab unity can advance this land toward independence and true freedom, toward progress and efflorescence.

Despite what some might assume, this sentiment was not confined to the secular left. A coalition known as the United Religious Front — composed of the religious Zionist Mizrachi party, the non-Zionist Agudat Yisrael, a range of yeshiva deans, the Hasidic rebbes of Belz and Ger and a host of municipal rabbis — published a broadside in 1951 that laid out its vision for the new state. While calling for the Torah to serve as a key pillar, the poster also insisted that the state be fully democratic and recognize the complete equality of non-Jews as a matter of nationality and religion. The following are two of the planks in its platform:

THE DEMOCRATIC STRUCTURE OF THE STATE: BASIC RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS. “Beloved is Adam (all humanity) who was created in God’s image” (Avot 3:14). We are commanded to guard with extraordinary care the sanctity of life, the freedom and the dignity of every human being. It is the task of the State of Israel to take pains to assure that the rights of the individual, and his/her freedom of speech and conscience, will not be compromised.

THE DEMOCRATIC STRUCTURE OF THE STATE: BASIC RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS. “Beloved is Adam (all humanity) who was created in God’s image” (Avot 3:14). We are commanded to guard with extraordinary care the sanctity of life, the freedom and the dignity of every human being. It is the task of the State of Israel to take pains to assure that the rights of the individual, and his/her freedom of speech and conscience, will not be compromised.

RIGHTS OF ETHNIC AND RELIGIOUS MINORITIES. In the State of Israel, full equal rights shall be extended to all citizens irrespective of their religion or race. Most especially, in the wake of our suffering and torment through millennia of wandering among the nations when we were bereft of civil rights, we ought to remember the exalted morality captured in the words of our Torah: “A sojourner ( ger ), you are not to oppress: You yourselves know the feelings of the sojourner, for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9).

RIGHTS OF ETHNIC AND RELIGIOUS MINORITIES. In the State of Israel, full equal rights shall be extended to all citizens irrespective of their religion or race. Most especially, in the wake of our suffering and torment through millennia of wandering among the nations when we were bereft of civil rights, we ought to remember the exalted morality captured in the words of our Torah: “A sojourner ( ger ), you are not to oppress: You yourselves know the feelings of the sojourner, for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt” (Exodus 23:9).

The passage of time has not been kind to these notions. Citizens in Israel today confront stiff challenges to the values of democracy and equality. Rather than lapse into despair, they would do well to recover the range of foundational principles that were present at the birth of the state and are contained in the above texts. They represent an important antidote to the current scourge of chauvinism and a repository of some of the most exalted ideals of the Jewish and Zionist traditions.

Chaim Seidler-Feller, who recently completed his fortieth year as director of UCLA Hillel, is Director of the Hartman Fellowship for Campus Professionals. David N. Myers is the Sady and Ludwig Kahn Professor of Jewish History at UCLA. Both authors are members of The Third Narrative’s (Ameinu’s signature initiative) AAF and SIP.

All photos are courtesy of Chaim Seidler-Feller